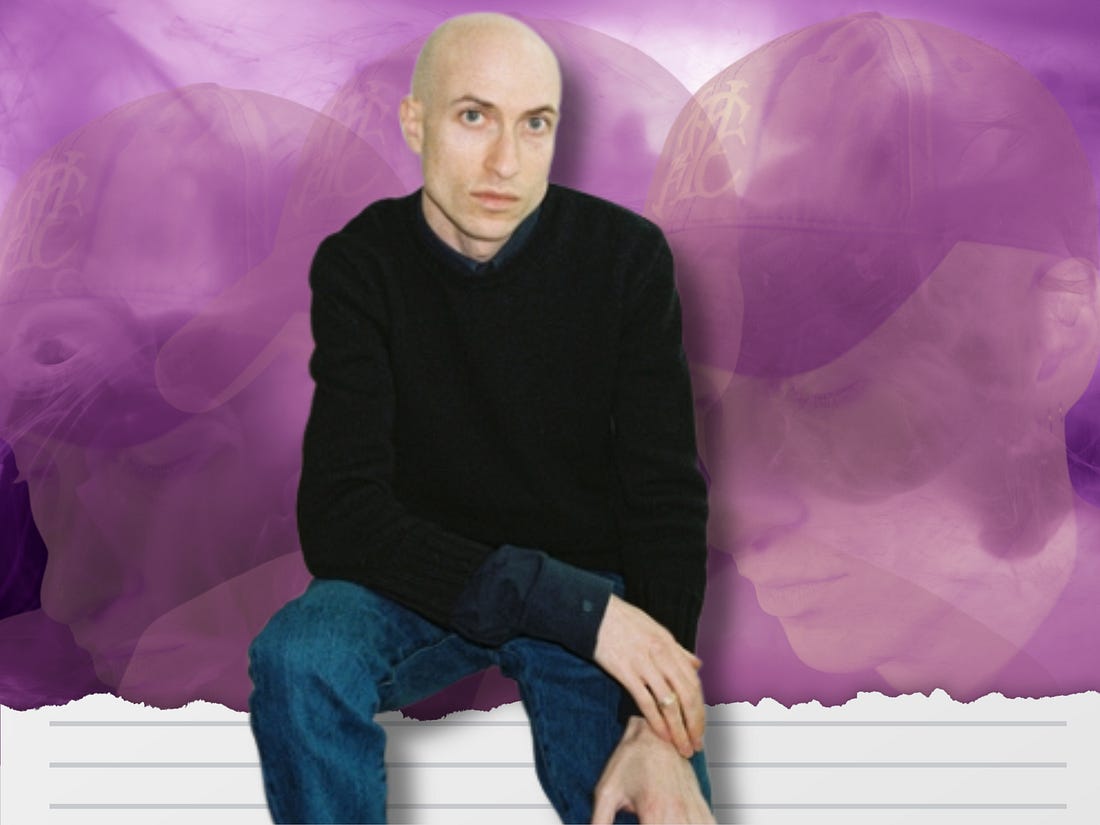

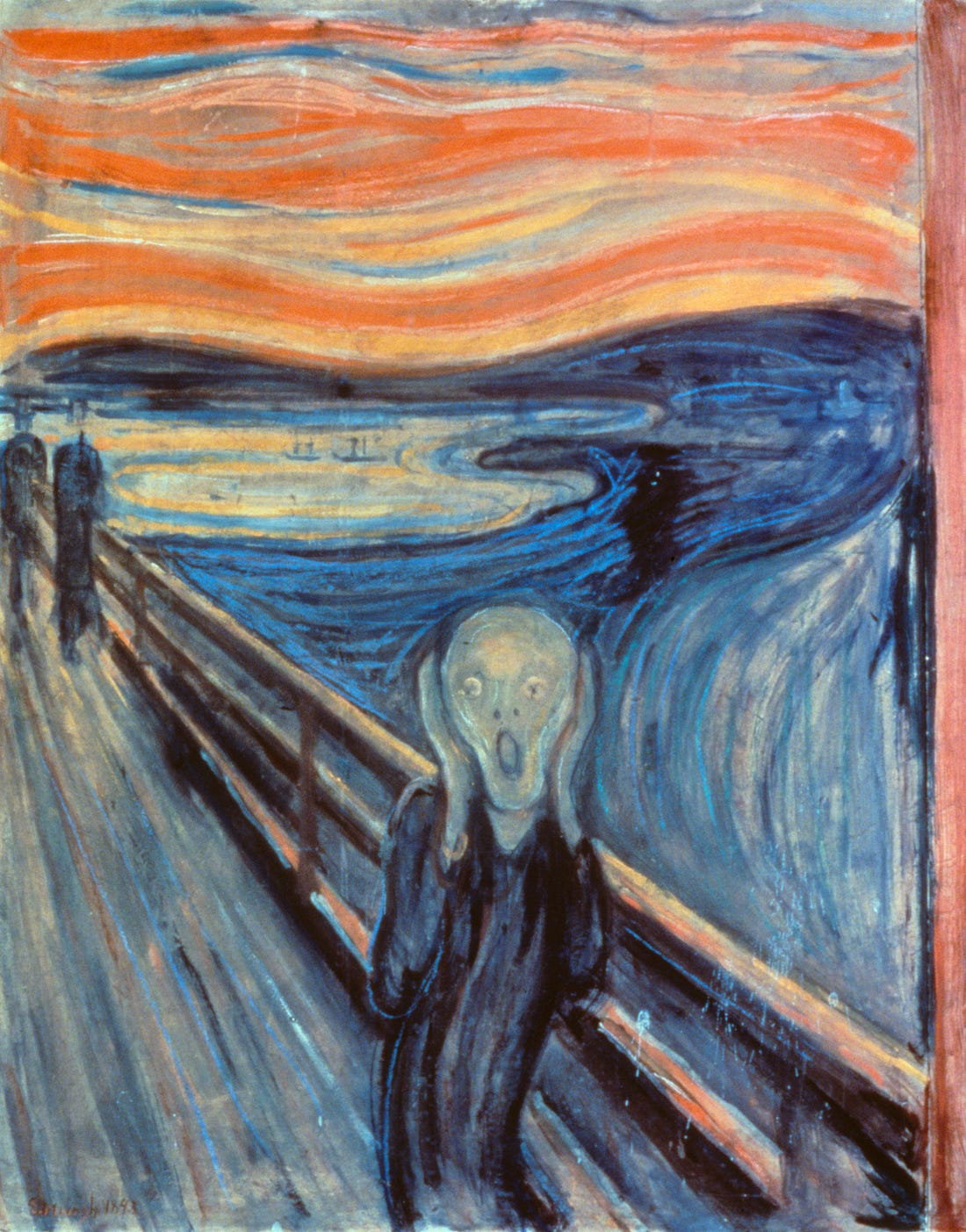

'The Brutalist' Score: An 'Extreme Piece of Work' for an Extreme FilmComposer Daniel Blumberg on his close friendship with director Brady Corbet and their painstaking collaboration on the epic dramaRob LeDonne recently spoke with Sing Sing’s Oscar song nominees Adrian Quesada and Texan Abraham Alexander, Oscar winner Kevin Macdonald about One to One: John and Yoko, nominees Diane Warren (“The Journey”), Elton John and Brandi Carlile (“Never Too Late”) and the husband-wife duo behind the music of Emilia Pérez. He’s at rob@theankler.comIt’s Valentine’s Day and for the occasion, it’s a column devoted to the music of ... The Brutalist? While it’s not exactly an escapist romcom, the acclaimed epic starring Adrien Brody was a passion project for all involved, including the Oscar best picture nominee’s composer Daniel Blumberg, who spoke to Notable this week. Also nominated for his work on the film (and a strong contender for the BAFTA score prize on Sunday), Blumberg went to the ends of the earth to achieve his singular sonic vision, even going so far as to record specific reverb echoes in an Italian marble quarry. But as he tells it, it was all because he wanted to do the best job he possibly could for his friend, The Brutalist director Brady Corbet. “I’ve known Brady for years and we’ve been through a lot together emotionally,” says Blumberg, who met Corbet in London about a decade ago, when the budding American auteur was making his first film there. “I wanted to repay him for being a beautiful friend,” Blumberg says. See, I told you this would be a fitting interview for Valentine’s Day. Speaking of love (and I hope it’s not too soon to use that word), which 2024 films do you have a passion for? If you’re an Academy voter, you only have until Tuesday, Feb. 18 to get your ballots in. But if you’re a civilian, you have much longer to make your picks in The Ankler’s first-ever Prestige Junkie Oscar Pool. Sign up here, and you can tweak as many times as you like up until the Academy Awards on March 2. While it may seem like a million years ago, this is the first Notable since the Grammys, where the big takeaway at the Grammys was Beyoncé’s long-time-coming Album of the Year win for Cowboy Carter. Meanwhile, regular Grammy winner Taylor Swift walked away empty-handed, and don’t ask her how the Super Bowl went, either. Other notable winners included Kendrick Lamar (who had a very good Super Bowl) and best new artist Chappell Roan, who had the audience hanging on her every word as she devoted her speech to mental health advocacy in music. Turned out she made an impact: Just yesterday it was announced that UMG is launching a Mental Health Fund with the Music Health Alliance. It’s been a big music week in NYC too. Last night marked the third and (supposedly) final night of Paul McCartney’s shock intimate residency at New York’s tiny Bowery Ballroom. I was lucky enough to be one of the 575 in the audience for Monday’s debut, for which I was given 90 minutes’ notice to get my butt there. Surreal was the word of the night, with McCartney delivering indelible classics like “Hey Jude” and “Hard Day’s Night” with a seven-piece band and songs like “Blackbird” with simply an acoustic guitar. “That was a blast, and you were the blasters,” he said to close things out; a fantastic line if I’ve ever heard one. McCartney is also part of SNL’s big anniversary special on Sunday (along with Paul Simon, Sabrina Carpenter, Bad Bunny and many more), but ahead of that historic night comes tonight’s SNL50: The Homecoming Concert, with performances promised from the likes of Cher, Lady Gaga, Chris Martin, David Byrne and Lauryn Hill, all produced by none other than Lorne Michaels along with Mark Ronson. I don’t know about you but I’ve been gobbling up all of the SNL50 content being churned out these past couple weeks, and the undying passion driving the people behind the show is the same kind of intensity that powers a towering piece of work like The Brutalist, Corbet’s three-hour-plus epic drama about a Holocaust survivor who becomes an architect in New York. Blumberg really poured his heart and soul into its complex musical world, with a blend of jazz, classical and electronic influences. It’s a stunning achievement, considering the thirtysomething virtuoso originally enjoyed life in the English experimental music scene and had nary a dream of working in film. It was fascinating to hear about his process and path to such a milestone achievement.  Rob LeDonne: Congratulations on the nomination. Have you noticed a difference in the opportunities coming your way since it was announced? Daniel Blumberg: Well, I am deep in post production on Brady’s partner Mona Fastvold’s film at the moment. They both wrote a new film called Ann Lee, about the Shakers; it’s a musical and Mona directed it, but she’s in the edit at the moment. So it’s been quite interesting to be working on this project and then also reflecting on the work that we did for The Brutalist. Brady’s such a close friend, so I’m just really happy for him that people are engaging with the work. You never know how people are going to respond. I work with a lot of musicians who make extraordinary work and sometimes it’s not very visible. So it’s very fascinating to see the different scales of how work is seen or heard. RL: That must be invigorating for you to go back and forth talking about creativity and actually being creative. Has this process of Brutalist reflection affected your work? DB: The way that I work is sort of bespoke for each project. I did a lot of the writing before The Brutalist came out, so between that and Ann Lee, it’s definitely not only a different set of instrumentation between the films, but also a different era that the films are set in. But it’s encouraging working on something else [amid The Brutalist’s acclaim]. You sort of think, “Yeah! Just keep going.” RL: You’ve said the way you work is to bring in musicians and create situations where they can be free. How do you go about letting a musician be free, and where did that idea come from initially? DB: Well, it depends on what situation you’re working in or who you’re working with. For example, someone like Axel Dörner, who played trumpet on the Brutalist score, he developed a lot of very specific and exciting techniques, and he’s very influential to other trumpet players. So inviting him to play on the score was inviting him as an artist. I’m trying to create a situation where he can be Axel Dörner, but within the context of the film or the music that I’ve written. So if I bring a theme into a section or if I am aiming to create music for a scene that’s a certain length, there are these limitations, but it’s also giving space to someone like him to work. Quite a crude example of it is the scene in the film where Brady wanted to shoot the scene to a live band. I knew what theme I wanted them to play and we talked about the sort of era of jazz that we wanted to invoke, but we wanted to create an environment where they’re actually playing music and not sort of reading notes or looking at a metronome. The music is having this impact on the way everyone’s moving in the room and then that has an impact on how Brady’s moving the camera. So when you’re watching it in the cinema you’re actually experiencing something that’s literally sort of unraveling before your eyes. RL: For people who are unfamiliar with your story pre-Brutalist, you’ve recorded music under Cajun Dance Party and Yuck, and are a part of this English experimental music scene. You didn’t score your first film until 2018. Was scoring films a long-harbored dream, or a facet of the evolution of your career? DB: It was definitely not a plan to score films at all. I fell in love with cinema when I was 17 when I literally stumbled into a Krzysztof Kieslowski film, this Polish director. I bought a DVD of his and it changed my life. It really had a profound effect on the way I saw the world. So I watched as many films as I could, and it was this mystical thing for me; these experiences like seeing Cassavetes for the first time. I had no idea how films were constructed and I wasn’t really listening to film scores at all. I would come out of the cinema and really be thinking about the director and what they wanted to make. I got into film scoring through Brady, because when he was making his first film he invited me to the scoring session. And Mona asked me to score her last film, The World to Come. I learned a lot and it was inspiring. RL: What was it like to watch the film and see this vision brought to life? DL: Well, I watched it many times with Brady doing the post-production since I was obsessed with how the arc of the dynamics would play out. So I actually sometimes would have to watch the whole thing just to see if one cue was the right dynamic. I watched it over and over again. But when it screened at Venice, it was actually really tough to watch because I was very nervous at the time. It was actually quite difficult. By the end, it was very rewarding for me, with everybody clapping towards Brady. I was really happy for him because he put his entire life into the film, and I found it really moving because they were giving him a thumbs up and saying, “You did it.” RL: Were there any other film scores that inspired you? When I was listening to the album today, it reminded me of some of my favorites, like Hans Zimmer’s score for The Dark Knight or Clint Mansell’s for Requiem for a Dream, both of which can both be so unsettling and give the audience a sense of foreboding. DB: I can’t speak to those scores because I haven’t seen those films and I don’t really listen to scores particularly in general. But Hikaru Hayashi’s score for The Naked Island is something that I come back to a lot. I just love the film, it’s beautiful. It’s an example of a theme being relentlessly explored. It always comes back to this beautiful theme, and every time I listen to it, I’m just there. The idea of creating a theme that can take you through the three and a half hours of The Brutalist was quite an important goal. So in retrospect, I think that was an inspiring score. RL: Some sequences of your score are very innocent and subtle, while other parts of it like on “Overture (Ship)” sound like a horror movie. I feel like I’m going to hear people screaming in the background. It reminded me of the Edward Munch painting The Scream. Does that ring true to you or am I the crazy one? DB: No, it’s really nice that you mentioned Munch. There’s a biopic about him that’s one of my favorite films ever made (1974’s Edvard Munch), and I actually played in his museum in Oslo twice over the last few years and I’ve seen The Scream there. But don’t forget for “Overture (Ship),” László Toth (Adrien Brody) is actually on a ship arriving from the Holocaust, basically, to New York. So you really have to take into account the weight of these characters’ experiences. With the sirens at the start, they’re brass sirens played with tubas and trumpets and trombones. But you try to speak to those experiences in almost a respectful way, you don’t want to make it bombastic. We’re always trying to push ourselves to make an extreme piece of work, basically because the film he made is extreme. RL: You created this on a shoestring $50,000 budget. Knowing what you know now, would you have liked a bigger budget or do you think the limitations pushed your creativity? DB: Well, it was the biggest budget I’ve ever had to make something. I come from a place where, just with musicians, we’re used to working with limited resources and to make do with those resources. A lot of the artists who I work with are quite poor. They either have to play lots of shows or they have to have other jobs. I had to put a lot of, basically all of my money into the music; sell gear and do gigs to fund it. But it was a sort of pact that I made to myself to basically try and do the best thing for Brady I possibly could. My general aim was to get to the end of it and think that I tried everything I could to make it good. I definitely came out of it with that feeling — but yeah, if I had more money and if the budget was bigger, I just would have been able to pay people more, like our [mixer] Pete Walsh; I worked on the mix with him for months. But creatively speaking, I would never think it could be in any way different. There was nothing that I would change. I’ve known Brady for years and we’ve been through a lot together emotionally. I wanted to repay him for being a beautiful friend. He’s exactly the same as me in terms of his life and his work. He’s very dedicated to his work, and that’s sort of the way that he navigates his life. And that’s been the same for me for the last 20 years as well, for better or for worse. I mean, it’s embarrassingly related to what The Brutalist is about. The film is literally about pushing yourself to make something. Follow us: X | Facebook | Instagram | Threads | Bluesky ICYMI

The Optionist, a newsletter about IP |

'The Brutalist' Score: An 'Extreme Piece of Work' for an Extreme Film

14:45

0