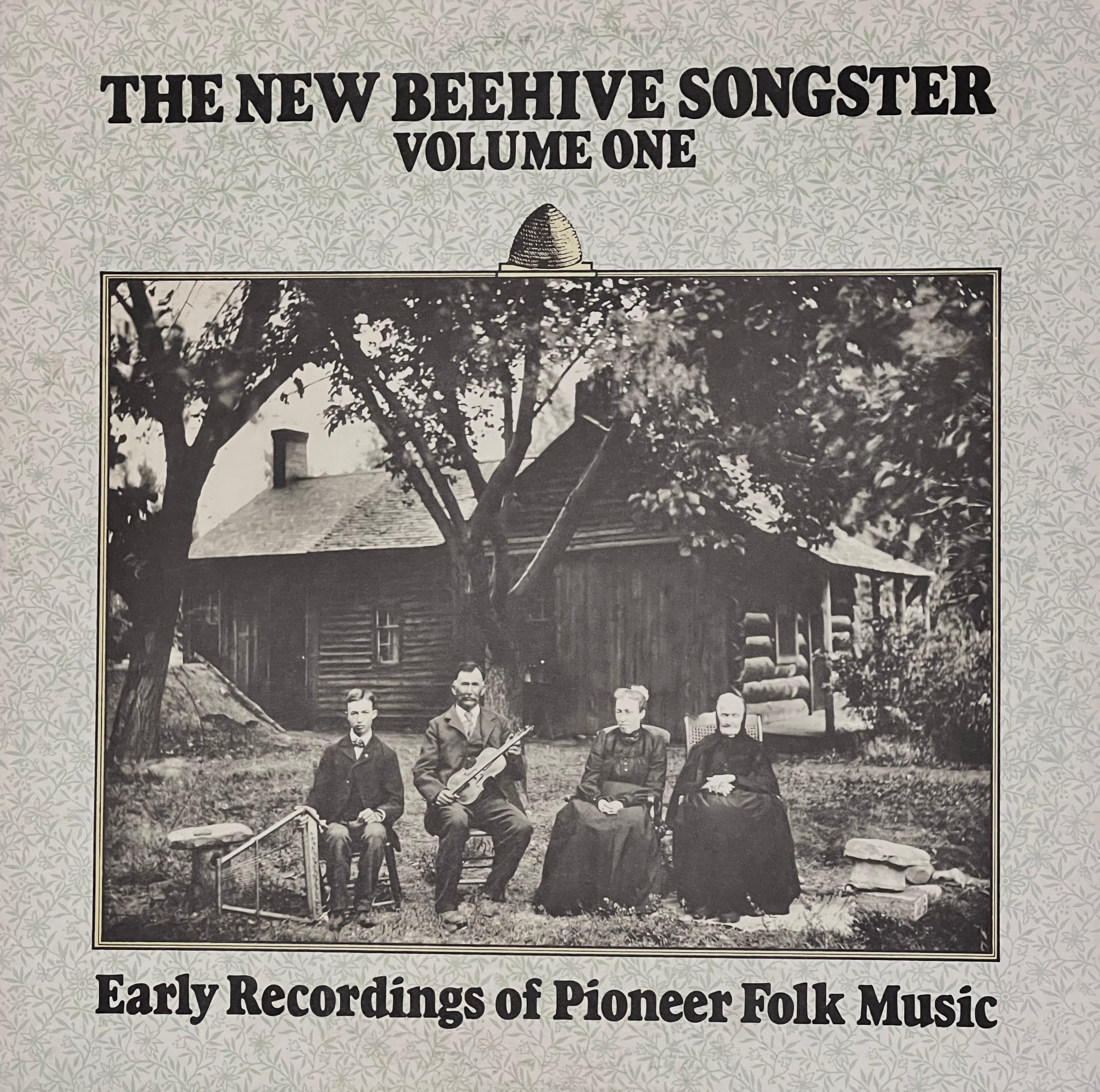

The first folklorist to record the traditional songs of working cowboys was John A. Lomax. He’d grown up on a farm on a branch of the old Chisholm Trail in the 1870s, where he heard the calls, yells, yodels, and songs the cowboys sang as part of their work. He never forgot those dramatic scenes from his childhood and even wrote the lyrics he heard. Many years later he took those songs to his literature professors and even later published books of the songs he collected. It was not an easy-sell to convince his professors and publishers that the songs of cowboys had any merit whatsoever. Yet, Lomax believed deeply that the songs of ordinary people were important to the American story. It was a radical idea. By 1910, he was making actual sound recordings of cowboys at the White Elephant Saloon near the Fort Worth Stockyards using an Edison wax cylinder recorder, asking cowboys to sing into the big lily-like horn. The astonishing thing, besides the wonder that he got cowboys to comply with his wishes, is that most of these songs contained no instrumental backup, no production, no rehearsal, and no expectation of fame and fortune. They were pure, unadulterated voices moved to song, pure as birds in the morning. John Lomax died the year I was born, 1948, but not before he and his young son Alan had traversed the south recording folk songs, including work songs and the blues at prisons, fiddlers up obscure hollers in the mountains, and ancient straight-postured ladies who recalled old ballads that had come from the British Isles a hundred years prior. The Lomax’s and others had started a new movement that resonated even in Utah, where I was born. Within a couple of years on either side of my birth year, Utah folklorists Thomas Cheney, Lester and Barbara Hubbard, and Austin and Alta Fife were recording folk songs that had come to Utah from the old country and newer songs, many that were commentaries on the Mormon experience. These songs were sung by the sons and daughters of Utah pioneers. And almost all the songs contained no accompaniment. In college, I found every excuse to avoid homework. My favorite diversion was to climb the stairs to the top floor of the University of Utah Library, where Special Collections was housed. There, I’d ask the attendant if I might go into a backroom where there was a tape recorder, which I’d thread ¼” magnetic tape from the full reel on the left to the empty on the right. Then I'd flip the lever to PLAY, and the sound of old scratchy acetate records copied to magnetic tape immediately enveloped me. These were folk songs recorded by Lester Hubbard from ancient history (anything before my birth). I don’t remember how I knew I could ask to listen to these recordings. There were dozens of tapes, and I learned later that the Hubbard’s had collected over 1000 songs, 250 of which went into the published collection Ballads and Songs from Utah. For Hubbard, the ancient ballads from the British Isles, known as the Child Ballads, were the pay-dirt of folk song collecting. The sound recordings were made merely for reference, so words and melodies could be captured. There was little intention of celebrating the artistry of the performance. But what I heard in each voice were generations of experience, musical style, and a literal time machine of meaning. I kept a notebook tracking the songs I liked. In the back of my mind, I was eager to adapt these songs to the old-time string band music I played, a music with a distinctive southern mountain sound to it. In 1972, my band, the Deseret String Band, made an album titled “Utah Trail,” made up mostly of songs from the Hubbard’s fieldwork. Later, along with Tom Carter and Jan Brunvand, we released vinyl LP’s in two volumes, titled “The Beehive Songster,” which contained Utah field recordings from various sources, mostly the Hubbard and Fife Collection. We released these records around the bicentennial of 1976. Later, when I became Utah’s state folklorist, I met and worked with Bess Lomax Hawes, who headed the Folk Arts Program at the National Endowment for the Arts. The youngest child of John Lomax, she became a friend and mentor. She also introduced me to her famous brother, Alan. Both Bess and Alan agreed to give keynote addresses in the early years of the Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko. The both talked about the family’s experience with cowboy folk songs. I’ll never forget accompanying Alan to a daytime performance of cowboy singers. As we left the show, I noticed Alan was silent and seemed to fume about something. Finally, he exclaimed, “damn the Viennese.” For good effect, he said it again but with more scorn in his voice, “damn the Viennese.” I was curious, but I was also cautious because Alan Lomax was known for his temper. I asked anyway, “I don’t understand?” He looked at me and simply replied, “They put songs into a strict rhythm, and it ruined it.” Until that moment, I had never thought of those unaccompanied songs as having a distinct style apart from songs accompanied by guitar, banjo, or piano pounding out a beat. But the more I listened, the more I realized something had been lost. I don’t know why the Viennese got the blame, but I’d guess it had something to do with Waltzes sweeping the world back in the mid-nineteenth century, bringing dance rhythms to most popular songs. As a musician, some of the glorious moments of playing have been for people dancing. At its best, it’s like the dancers join the band as we all strive for the magic. Years ago, we produced an album by the Snake River Outlaws compiled from audio tapes saved from radio shows broadcast live at a popular dance hangout in Missoula, Montana. The tapes were recorded just after the Korean War, and listening to them, we realized the crowd would dance to anything from sad old love songs to a hoedown. It didn’t matter; they were there to dance. You could almost feel the hormones in the room. I don’t hear that in today’s dance music, but every generation believes it invented sex. I’ve been thinking about all the great old unaccompanied songs I’ve stuck my guitar or banjo behind to kick them up a notch. I don't mind stripping away the instruments and letting my bare voice carry the tune, and lately I've come to be fascinated by the vast array of unaccompanied singing traditions. For my latest album, Cowboy Sutra, I wanted to compose a setting for the songs which would allow vocalizing without the guiding force of rhythm instruments and that’s why I picked the drone of the harmonium to accompany the songs. There are songs that move to a strict rhythm but others that do not. Also, I found with my harmonium I could think about using other instruments to provide a musical environment to each song rather than just rhythm. I hope to put a playlist together of great unacompanied singers from a veriety of traditions to share on the Loose Cannon Boost. If you have a suggestion of a song and singer please leave a comment. Soon, I will release a song a week from the new album here on the Loose Cannon Boost. I can’t thank all the people who have taken out a paid subscription to support and follow the saga of this song cycle. I’ll end by sharing one of two unaccompanied songs I’ve recorded and released. This one is off my self-titled album and is based on an 1860’s poem, “the Blizzard,” written by Eugene Ware. Flavia Cerviño Wood played the violin. CLICK HERE TO LISTEN You're currently a free subscriber to Loose Cannon Boost. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

A Tribute to the Unaccompanied Song

16:28

0